Actress Deepika Padukone endorsing an Oppo smartphone.

“The government should be more supportive of their people.” Narendra Bansal, founder of Intex Technologies, an Indian technology company that was the second largest mobile vendor in the country by volume less than two years ago, pleaded earlier this year. Bansal is one of several top executives from Indian smartphone vendors who are furious at losing market share to Chinese companies in the past two years.

In the plea, Bansal – alongside chief executives of other Indian smartphone vendors like Micromax and Karbonn Mobiles – accused Chinese smartphone vendors of dumping low-cost smartphones in India, making it tougher for the local businesses to survive. The government should introduce an “anti-dumping” duty on such phones, the CEOs suggested. “Every child needs hand-holding by their parents,” Bansal said at the time.

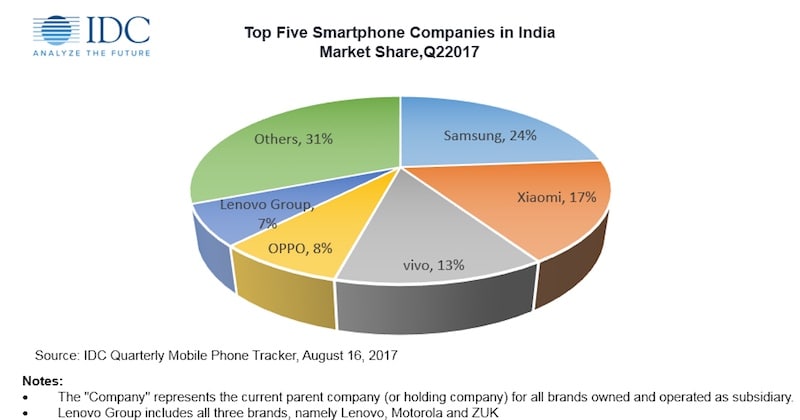

Over the past two years, Indian smartphone vendors have lost about 35 percent of the market to Chinese companies. Just two years ago, Micromax, Karbonn Mobiles, Lava and other local players had more than 54 percent market share, according to data from marketing research firm Counterpoint. In the quarter that ended in June this year, Chinese players had surpassed 50 percent of the market for the first time in India since entering the nation, according to IDC.

The outcry from the Indian smartphone vendors was, in a way, a public admission that they could not fight back against the Chinese brands – with increased marketing, cutting down the retail price of their phones, and embracing the online strategy, all falling short. But to understand how it all happened, you will have to look at the history of the phone business in India and the ever changing relationship between the companies.

Building ‘Indian’ brands

A decade ago, when Apple was about to announce the first iPhone, mobile phone stores in India were still filled with feature phones, and smartphones as we know them today were still a few years away. In China and Taiwan, two of the largest electronics manufacturing capitals of the planet, the growth of feature phones was slowing down, says Jayanth Kolla, founder and partner at Converence Catalyst. Around the same time devices manufacturing business at both the places was starting to get commoditised, leaving little scope for profits to the companies, he said. “It became a cottage industry there. It was easy for any small company to try its own hands at manufacturing mobile phones,” he added.

While Steve Jobs was attempting to revolutionise the smartphone industry, a revolutionary idea of sorts was also being explored at the headquarters of the Indian mobile industry of the time. For years, these companies had served as distribution partners for Nokia, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, LG, and other companies.

Could they now make their own feature phones? The executives wondered. That was a monumental moment in India’s mobile phone industry, Kolla said, as Micromax, Spice, Lava, and Jaina Group (which would later be rebranded to Karbonn Mobiles) made their foray into the OEM space. Several Indian brands partnered with Chinese Original Design Manufacturers (ODMs) to explore what is known in the industry as the white-labelling deal. One company designs and manufactures the phone, another puts its name on it.

These Chinese ODMs brought two areas of expertise to the table: first, they could manufacture feature phones at record low prices, giving Indian vendors a major weapon to fight back offerings from Nokia, Motorola, and several other international giants that had in-house manufacturing capabilities.

Second, Micromax and other Indian vendors were able to bring new models to the market in a much shorter period of time. While Nokia and other companies typically took more than a year in conceptualising, manufacturing, and then bringing the phones to the market, Kolla told Gadgets 360 that the Chinese ODMs were able to complete that process and hand over the inventories to Indian smartphone vendors in three months, and sometimes less than that.

And thus began the trend of “dumping” low-cost feature phone models in India, and quickly gaining some market share in the country. Micromax and others began to spend big money on marketing, targeting two things Indians love the most: cricket and Bollywood.

However, it didn’t take long before shareholders and consumers started to complain. All these feature phone models looked alike. Investors kept suggesting to companies that they need to make major investments in research and development, one way to differentiate from the competition.

No product people

The problem however, was much deeper, a top level executive who has worked with one of these companies told Gadgets 360. Micromax and other local Indian companies didn’t have the right set of people to lead the companies, the person said. They were traders, he said, adding that nobody had the experience with – or much expertise in – products.

Co-founders of Micromax

“The problem was that none of their [Micromax’s] founders were product people. They had expertise in marketing and distribution,” the executive said. But while the soul-searching for the right candidate would get underway, something else was on the horizon: smartphones.

By late 2010 and early 2011, the market had started to demand smartphones. And that changed everything. First, it put most Indian companies on a level playing field with the international giants of the time, as all of them were trying to figure out how to crack the smartphone game. But at the same time, the call from investors to Micromax and other Indian companies to make investments in research and development continued to come in, people familiar with the matter told Gadgets 360.

Getting into the smartphone space, the Indian brands brought in one feature that would set the tone for the industry in the coming years: dual-SIM smartphones. At the time, data and voice calls were much costlier in India, and people often swapped SIM cards to optimise their costs. Fast forward to 2017, and more than 90 percent of smartphones shipped in India have dual-SIM capability, according to Counterpoint.

Micromax and other Indian companies further leveraged their relationships with Chinese ODMs and started to offer low-cost smartphones in the country. These phones sold well as much of India’s population eyed their first smartphone, but the devices still looked mostly identical, with similar hardware and software capabilities.

The market demand for low priced phones was very high, and Indian smartphone vendors were able to cash in on that. From a less than than 10 percent smartphone market share in late 2010-mid 2011 to surpassing 50 percent in 2015, the companies were finally in good shape. And then came the turning point.

After years of continued growth, China’s smartphone market was getting saturated, making it difficult for Huawei, Gionee, Xiaomi and other local companies to maintain growth. Hence, many of these companies had begun to look elsewhere: with India and Indonesia, among a handful of other regions, soon becoming their focus markets.

India made sense to many, especially Vivo, Oppo, and Gionee, since they had been the original ODM partners of Micromax and many other Indian companies. “They had all the insight on what kind of smartphones Indian consumers want. They already knew what kind of strategies to put in place from years of their experience in China, the world’s largest smartphone market,” Converence Catalyst’s Kolla said.

For the first few months, Indian smartphone vendors didn’t show much concern about the growing competition. In fact, at Rise conference last year, Micromax co-founder Vikas Jain announced plans to enter China, a move that signalled an intention to take the Chinese companies head-on.

Micromax co-founder at Rise conference last year.

Photo Credit: Rise/ Flickr

But soon enough, as more smartphone vendors – like Xiaomi – began to enter India and they started to gain ground in the country, a sense of panic had set in. The Indian companies finally began to bring in professionals from other companies. For instance, Micromax hired Vineet Taneja, a veteran of Samsung and Airtel.

Things should have improved, but they didn’t. People like Taneja couldn’t do much. Their hands were tied, according to several top executives and insiders who spoke to Gadgets 360 on the condition of anonymity.

“The role, or the direction, or the way the professional management was running, was never really justified,” one of them said. At the end of the day, founders made all the calls, even for smaller tasks, people said, with one of them describing the culture of the biggest Indian mobile vendor of the time as “cowboy maverick.” The person added that Micromax should change that culture if it wants to succeed in the future.

Chinese brands offered original designs

“By 2015, smartphones had started to get commoditised. It had become a specification game,” another former executive with an Indian smartphone maker said. “Chinese players had already seen the smartphone market in their own country. So they were more informed, more intelligent, and some of them had deep pockets.”

But what really pushed them ahead, the person – speaking on the condition of anonymity – said, was “Chinese guys were energetically building differentiations through design. It is wrong to say that Chinese guys came and spent a lot of money in the market. If you don’t have products, no amount of advertising will sell it. If you find a Vivo phone in certain shape and size, you won’t find an identical phone from Oppo. I mean, they copy, but they don’t all offer identical features.”

“That’s where the fundamental difference lies. In India, we are very good at scaling things. We copy and then we continue to make them cheaper. Through shared distribution, advertising, we quickly scale a product. But if you look at the success of all the Chinese players, they don’t really sell cheap phones, they actually sell differentiated expensive smartphones. They make better margins, and use that for marketing and retail,” the person added.

The executive added that among Indian companies, making nearly identical feature phones had become a norm. “Because the Indian players have shown no capability of original design, that’s one of the reasons people like me left. The promoters were unwilling to spend and look beyond. They say this is how we have done in the past, so we will continue to do that,” the person added.

“Chinese players came with clear strategies. We Indian guys never really had much strategy. We are tactical. We keep copying what the other one is doing. No wonder then when we fell, others immediately went the same path. Copying can only take you so far. You can make some money off for two to three years by putting things together sourced from China and sell here. But that sort of model is doomed to get disrupted.”

An insider at Micromax told Gadgets 360 the company had planned to spend a significant amount of money on building a host of unique software features in 2016, until the founders decided to can the idea to save money.

E-commerce to offline

India remains a large market for smartphone manufacturers. About 350 million people out of the country’s 1.2 billion popular currently own a smartphone. Just last year, more than 100 million smartphones were shipped in India, according to IDC.

One strategy that was particularly unique to Chinese companies was using e-commerce. Though most Indians prefer purchasing smartphones through offline retail – according to Convergence Catalyst nearly 80 percent phones are still sold offline – Chinese players in the initial years stuck to Flipkart, Amazon India, and Snapdeal. The move, Chinese companies said, would help them avoid logistics overheads. “What we did? We had all the offline retail presence in the world. But then we started to make online-only smartphones like phones under Yu brand,” one former Micromax executive said.

Xiaomi vice president Manu Kumar Jain at the company’s new flagship Mi Home retail store in Gurugram last month.

But as Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo started to gain ground in India, they began building the foundation for expanding their presence to brick and mortar stores. Xiaomi now sells phones through more than 600 retail stores in nearly a dozen cities in India. Last month, the company said it intends to reach 1,500 retail stores in 30 cities by the end of the year. The Chinese phone maker is ensuring that it offers the same pricing and support in its offline stores as it does through Flipkart, Amazon India, or its own ecommerce site Mi.com, which has become one of the leading online shopping portals in the country.

Oppo and Vivo have been more aggressive with their strategy in India. To expand their presence to tier-2 and tier-3 cities, which are still relatively untapped regions in the country, the two brands convinced merchants to rebrand their retail stores as Oppo or Vivo stores, handing out as much as Rs. 40,000 ($625) per month just for that, according to several retailers Gadgets 360 spoke to.

Additionally, both Oppo and Vivo were – at least until recently – offering much higher profit margin to retailers – as much as 30 percent in some cases, retailers said. The industry standard is five percent. So these incentives gave retailers more reasons to stock their shops with Oppo and Vivo phones, instead of Indian brands.

“It was just a money play,” another former Micromax executive said. “By our estimates, the industry was spending Rs. 500 ($8) per customer acquisition. We had a slightly different model and we were spending Rs. 200 ($3.2) on customer acquisition because we believed our creative quality was higher.”

“But these guys [Chinese brands] came in and started spending up to Rs. 7,000 ($110) per customer acquisition. They spent more than 400 crores (roughly $62 million) a year just on IPL sponsorships [a two-month-long cricket tournament]. 400 crores is more than double of what Micromax spends in whole of a year in marketing. And again, you have to realise, Micromax had larger marketing budget than Lava, and Karbonn Mobiles, and other Indian companies,” the person added.

In addition, Oppo and Vivo have also spent a huge sum of money to get top Bollywood and cricket stars — including Deepika Padukone, Ranbir Singh, Alia Bhatt, Hrithik Roshan, and Virat Kohli — to endorse their smartphones, and win sponsorships of big cricket tournaments such as IPL. Vivo has put 2,199 crores ($342 million) on IPL title sponsorship for a period of five years, a figure that is significantly bigger than what Barclays paid for the English Premier League, the world’s most watched sports league.

As a result of these efforts, Chinese companies have started to dominate. According to research firm IDC, Xiaomi had 17 percent of the market share in the quarter that ended in June. Vivo had 13 percent, Oppo had 8 percent, and Lenovo stood fourth with 7 percent. Samsung retains its top position in India with 24 percent market share.

Photo Credit: IDC

Adapting to India

All of the Chinese companies operating in India have additionally adjusted their logistics to better match the local policies. One such example is their participation in Make in India programme, an initiative from the Indian government that encourages companies to manufacture or assemble products in India.

This leads to creation of more jobs in India. To incentivise companies to manufacture in India, the government offers relaxations from several import duties. Close to 70 percent of handsets purchased in India now are manufactured locally, according to several marketing research firms.

“Increased local production has partly been prompted by goodwill, but increased taxation and import duties on components have also played a major part,” Raghu Gopal of CCS Insight told Gadgets 360.

Market anticipation is another key area where Chinese smartphone makers have been performing exceedingly well. Last year, when Reliance Jio launched with free access to Internet, the company sent hundreds of thousands of people rushing to retail stores.

Reliance Jio offers a 4G-only network, and hence it doesn’t work on smartphones that don’t offer support for LTE. Many smartphones, especially those made by Indian phone makers, back then didn’t have this functionality. “We were selling phones that maxed out at 3G support,” Rahul Sharma, a founder of Micromax told Gadgets 360 in a recent interview on the sidelines of launch of Canvas Infinitysmartphone.

“But overnight, the market changed from 3G to 4G. So at that time, a person who had never even purchased a 3G-enabled phone wanted to get a 4G-enabled smartphone to make use of the ‘free Internet,'” he added.

Arvind Vohra, the executive director of Gionee, had a much simpler explanation for the tremendous growth of Chinese phone makers in India. “Somewhere down the line, Indian companies failed to convince consumers that they have all the offerings they want in their phones,” he said. “As far as a consumer is concerned, they feel that superior product with top quality are being offered by Chinese players. By being consistent with product quality, Chinese companies have earned that mindset.”

Can a course correction happen?

The Micromax Canvas Infinity is the first smartphone the company has launched in the past six months in India, a major departure from its earlier strategy of flooding the market with multiple options – in 2014, for instance, Micromax shipped more than 30 smartphone models. “We turn around faster than any other company,” Vineet Taneja, the then chief executive of the company had said in an interview.

“You have to watch out for chinaman,” Micromax’s Sharma said as he unveiled the Canvas Infinity last month. It was a play on words – in cricket, chinaman is a ball from a left-arm bowler that turns the opposite way to orthodox left-arm spin.

Micromax employees at the launch of Canvas Infinity last month.

“We scaled down our efforts earlier this year to assess the strategy of Chinese companies, and buy ourselves some time,” Sharma said in an interview with Gadgets 360. “The way Chinese companies [specifically Oppo and Vivo] had been spending money, it was clear to us that there is no point fighting with them at the point,” he added. “But now as you know, their money is quickly disappearing (both Oppo and Vivo have cut down the incentives they used to offer to retail stores in the past two months, retailers say), we think it’s the right time to make a come back.”

Sharma said the company continues to believe in bringing high-end technologies to the mass. The company’s Canvas Infinity smartphone, for instance, has a 18:9 display, similar to those in Galaxy S8 and the LG G6 flagship smartphones, though its performance isn’t obviously at the same level. “We will prove again to people that we are a disruptive and aggressive brand,” he added.

Sharma also rejected the accusations from others in the industry that Micromax hasn’t invested in research and development. He told Gadgets 360, “We have invested heavily in R&D. We are the only company that has invested in more than 10 companies and startups. As for creating infrastructure, we are the only company that has three factories. And those are very large factories. We also have a design centre in Bangalore, and one in Beijing.”

When we asked for an update on the company’s plans to start selling smartphones in China, something Vikas Jain, another founder of the company, had said would happen this year, Sharma said the “the focus is currently on India right now.”

One of the former Micromax executives Gadgets 360 spoke to commended Sharma’s move. “The way some Chinese companies were spending money in India, it was a very smart thing to just wait and kill some time. If you survive as an organisation, and later one of your products becomes a hit, you can make a comeback,” the person said.

Karbonn Mobiles didn’t comment on the story. A spokesperson for Lava Internationals, who requested an additional week to reply after being given ample time to participate in the story, didn’t respond to our queries either.

Analysts at Counterpoint expect Indian smartphone makers to lose more market share this year. Former executives, as well as Gionee’s Vohra were optimistic about the future of Indian companies, however. “If they start evolving in terms of their products, I see no reason why they can’t succeed,” Vohra said.

[“Source-gadgets.ndtv”]