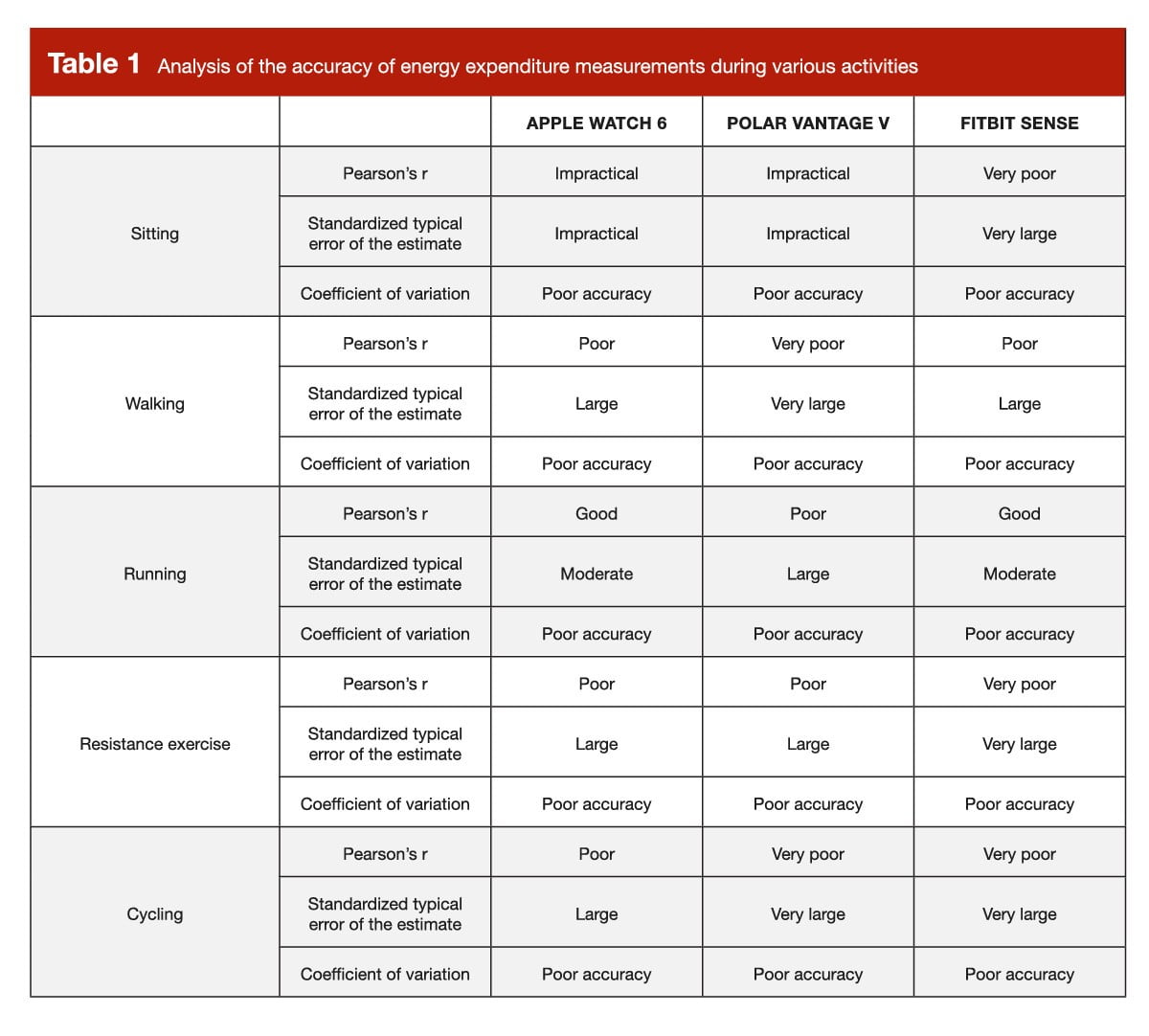

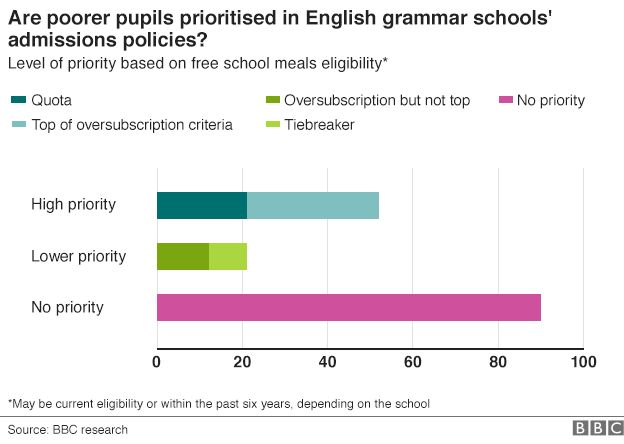

Fewer than half of England’s grammar schools give poor pupils priority in allocating places, BBC research shows.

An analysis of the 163 grammar schools’ admissions policies found 90 do not take account of a child’s eligibility for free school meals.

Ministers want to ensure new selective schools take in more poor pupils.

The Grammar School Heads Association said grammars were at the forefront of giving admissions priority to disadvantaged pupils.

Grammar schools – state-funded schools that select pupils on the basis of ability – are facing increasing pressure to become more socially inclusive, amid government plans to increase the number of them.

Grammar schools: What are they?

What will new grammar schools look like?

Critics of the expansion plans have focused on the low number of pupils attending grammar schools who are eligible for free school meals – used as a traditional measure of poverty.

But the BBC’s analysis of admissions policies suggests the raw percentage of free school meals pupils in grammars does not capture where and how things are changing.

The most recently published admission policies for applications for 2017-18 reveal the extent to which change is under way.

Quotas

To gain a place at these academically selective schools, pupils have to pass a test, which varies from one area to another.

Once pupils have passed the test score threshold, schools, if oversubscribed, allocate places according to their admissions policies.

The analysis revealed that 21 grammar schools set aside places in quotas for pupils from lower income families.

A further 33 give some degree of priority in their oversubscription criteria, while nine grammar schools use it as a tie-breaker for allocating places to academically matched pupils.

The five grammar schools within the King Edward VI foundation in Birmingham go furthest, with a quota policy allocating up to 25% of places to pupils who are eligible for pupil premium funding in order of their test scores.

This means children who have been entitled to free school meals, and therefore the pupil premium grant, in the past six years are considered before remaining places are awarded.

The policy has been in place for two years, so it will be some time before it fully alters the profile of the schools.

But not all quotas are as generous.

Urmston Grammar School, in Manchester, sets aside just three places out of an intake of 150 for pupils entitled to pupil premium.

The Skinners’ School in Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, gives five places, out of 150, to pupils eligible for free school meals.

Prof Anna Vignoles, from the University of Cambridge, described the research as “insightful”.

‘Deprivation levels’

However, she added: “Whilst quotas or other measures might help, the fundamental problem in the system is the very large gap in achievement between free school meals pupils, and others, at the end of primary school.”

Recent research from the Education Policy Institute showed grammar school pupils travelled, on average, twice as far to get to school as those attending non-selective schools.

EPI’s director of education data and statistics, Jon Andrews, questioned whether quotas could really make a difference.

“Simply allowing more disadvantaged pupils to attend grammar schools will not create the systematic improvement needed for a world-class education system,” he said.

“A policy to introduce quotas would be self-defeating.”

The government is consulting on proposals for new grammar schools, including asking what proportion of children from lower income families they should admit.

Its consultation document says: “Selective schools also need to ensure the pupils they admit are representative of their local communities.”

At Wolverhampton Girls’ High School, 5.6% of pupils have been eligible for free school meals in the past six years, but the local authority average is 43%.

The school is located in a relatively deprived area, but has no criteria in its admissions policy to give priority to children from poorer households.

Admissions code

Many grammar schools are sited in more affluent areas, but the BBC analysis suggests no clear correlation between their admission policies and the level of deprivation within a few miles of their location.

Some schools use postcodes in their admission policies to more closely reflect the local social mix, and they all engage with their local primary schools to encourage applications.

The Grammar Schools Heads Association said it had pressed for the changes to the government’s admissions code, which came into force in 2014, and made it easier for maintained schools to give priority to poorer pupils.

In a statement, it said: “2017 is consequently the first opportunity for most schools to make such changes to their admissions policy and many grammar schools have done so, with more consulting to do so for 2018.”

The Department for Education said: “Our new approach is not about recreating the binary system of the past or maintaining the status quo.

“We want to look at how we can ensure new selective schools prioritise the admission of pupils from lower income households and support other local pupils in non-selective schools to help raise standards.”

[Source:- BBC]